Wood

There is no material that I love more than wood-- with the delights that it provides -- from seeing the rich textures of tree bark or the dance of limbs caught by a breeze, to feeling the warmth of boards under foot or massage of woodgrain on fingers. While, in our current climate-change era there is a newfound appreciation for using wood as a material of carbon sequestration, what I still find most enduring is wood's ability to connect us viscerally and meaningfully to nature -- in ways that can delight all our senses.

Light

It is intrinsically human to find joy in the changing shapes of clouds overhead, the lull of ocean waves washing upon shores, and the mesmerizing tongues of campfire flames. Heading this list for me though is the dance of light and shadow from the sun itself. Whether it is the subtle color shifts from dawn to midday to dusk, or the accompanying changes in intensity and softness or harshness of shadows – the dynamism of the sun fascinates me. It is the ultimate presence that aminates life.

A Mentor

I consider architect Louis I. Kahn (1901-1974) – sometimes referred to as "the spiritual father of Modernism" – as my greatest mentor, although, because he had died 2-1/2 years before I ever heard his name uttered, I never actually meet him in person. Nonetheless, his writings, unbuilt projects, and completed buildings demonstrate his belief that continuing to question is, itself, the best answer.

His searching for the nature, or essence of things is reflected in an aphorism of his that I take to heart: What does a brick want to be?

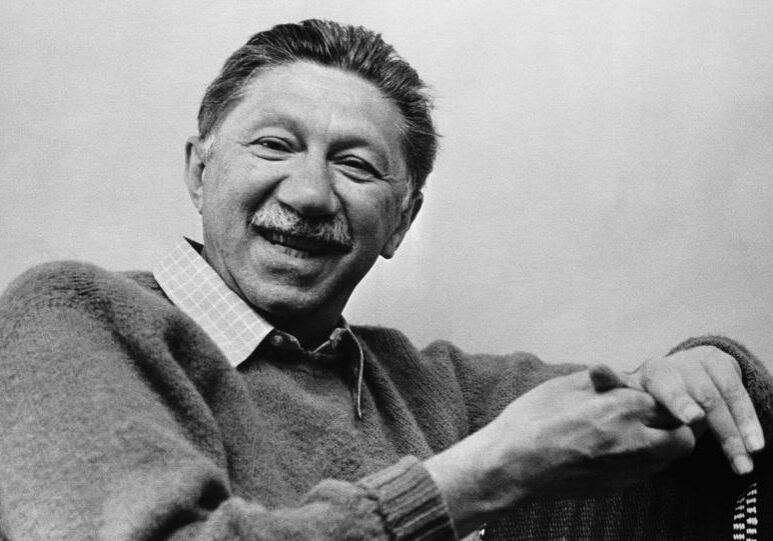

Psychology

I’ve always been fascinated by trying to better understand people’s needs and learn how to make the world a better place. The Hierarchy of [Human] Needs, formulated by psychologist Abraham Maslow in the 1940’s serves as the cornerstone to my practice of Wholeness Dwelling. I have found his later, eight-tiered model of development, as it proceeds from four deficiency needs to four growth needs, to be instructive for conceptualizing how architecture can promote “becoming your best self”.

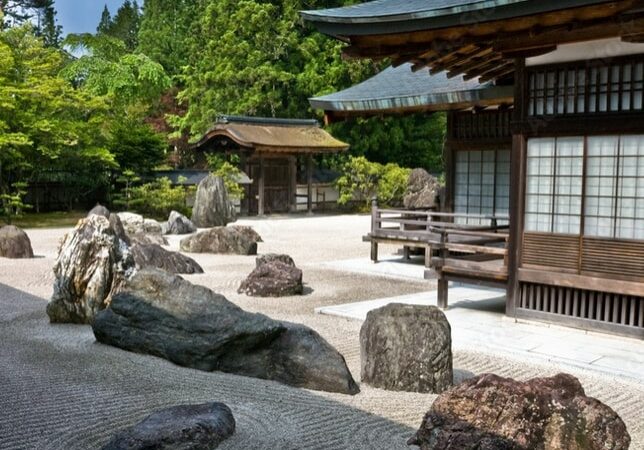

Japan

Although I was fortunate enough to be able to visit Japan several times while working on a new hotel in the Nikko National Park prior to opening my own practice, my interest in Japanese architecture began early, as a teenager, when I saw its influence in the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Not only do I continue to find the aesthetics of traditional Japanese architecture to be deeply moving, I am also inspired by many aspects of Eastern religious/philosophical thinking and view of nature.

Spirituality

It was having been raised in a metaphysical-based religion that shaped, in part, why I approach architecture as I do – seeking to connect to what is essential and timeless. However, in contrast to that, I’ve always instinctively been drawn to realizing grace and beauty in tangible earthly presence, accepting impermanence and weathering. It’s in the liminal space between eternity and the ephemeral, between idea and presence, that I feel we can find our lived experience of deepest meaning and sense of belonging.

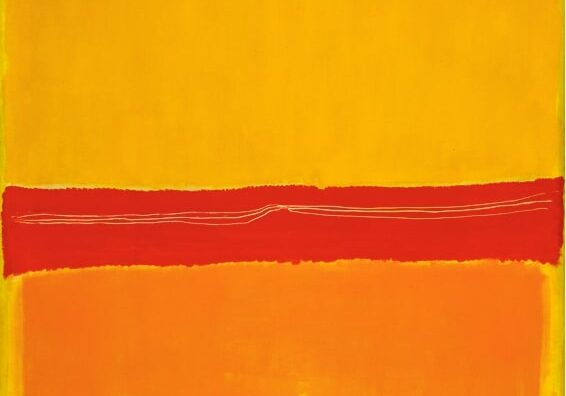

Art

Whether one’s art form is architecture, poetry, dance, or painting, it is most enduring and moving when experienced at a gut level – as intuitive feeling rather than through analytical thought. The works of the color field painters of Abstract Expressionism and artists of the Light and Space Movement, most notably Mark Rothko and James Turrell respectively, inspire my thinking as to how one can cultivate atmosphere as an emotionally uplifting presence within the dwellings we inhabit.

Travel

Growing up in upstate New York, while having grandparents on the west coast, afforded me an abundance of cross-country road trips. In addition to being awed by the majesty and immensity of nature – from geysers and rocky shores to deep canyons and towering redwood forests – I reveled in seeing both striking vernacular buildings and heroic engineering feats. Exposure to such diversity of nature and human endeavor inspired me to seek the presence of beauty wherever I find myself.

Scandinavia

To this day, my experiences during a full year of architecture school and travel abroad, continue to inform and enrich my practice. In particular, a semester in Copenhagen and travel throughout Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland gave me firsthand exposure to profound works by Jorn Utzon, Alvar Aalto and Arne Jacobsen – works expressive of the softness of Nordic light and achieving a poetic symbiosis of modernity, utilizing natural materials and what might be termed a regional sensibility.

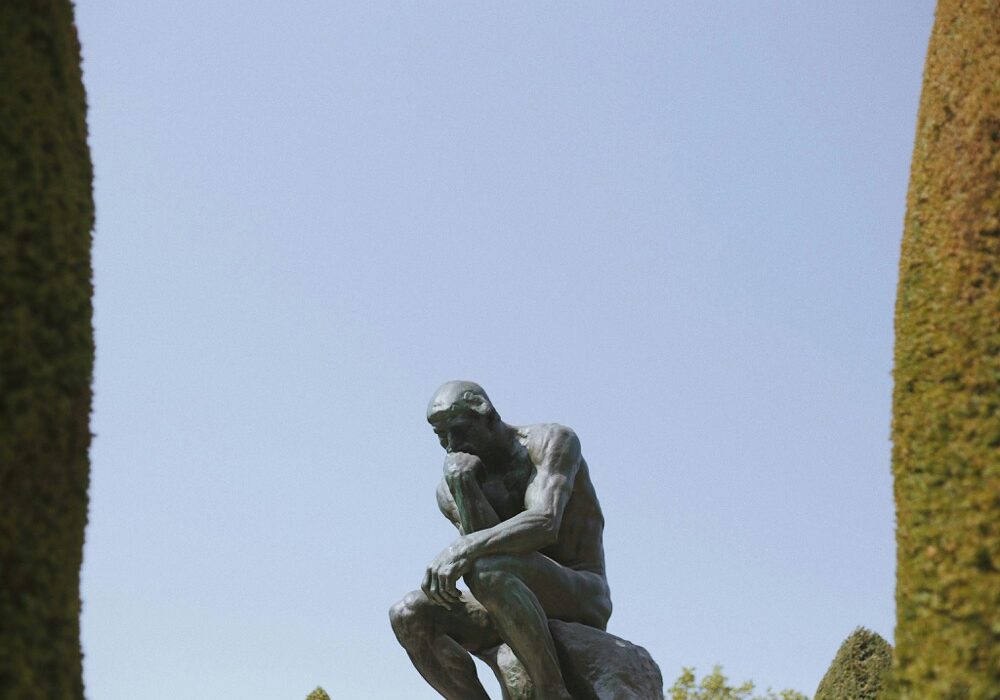

Philosophy

One might think that philosophy is an unlikely basis for informing architecture. However, delving into both phenomenology and existentialism has provided me with tools for shaping buildings which deeply reward firsthand experience and achieve resonance at a spiritual level. In fact, I see these fields of study as a means for cultivating a co-present awareness of immediacy and expanse that enables transcendent experiences. Achieving that is rare, but I find it to be an extremely worthy pursuit nonetheless.

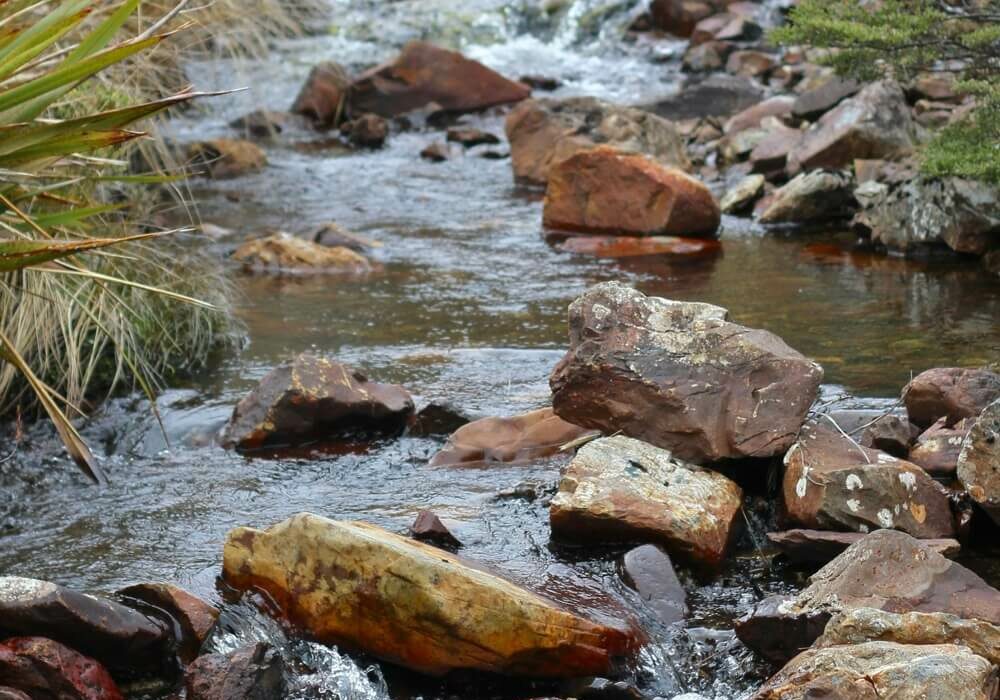

Nature

It’s common, at least in Western culture, to speak of humankind and nature as a duality – often celebrating nature as what is pure and good, and decrying human endeavor as misguided and tragic. I believe that there is but one nature, with humans being part of it. Our flaw is in seeking to extract ourselves from nature, rather than recognizing and living our interconnectedness with all things great and small. Our highest calling is to find and express our own nature while also respecting the nature of what surrounds us.

Food

How we prepare and eat food offers so many lessons for how we can dwell. The Slow Food movement in particular has helped shape my ideas of wholeness dwelling. Its placing value on the experience of food as primary – rather than convenience, speed or cheapness – is certainly applicable to how we can choose to live. In architecture too we can find delight in experiencing the richness of ingredients, connection to seasonality and having an ethical awareness towards other beings and our planet.